More Old Sutton Warriors

Tom Pye, Fred Feather and Eddie Feather

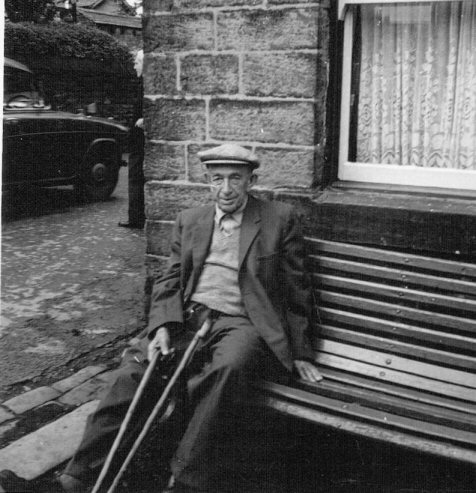

Fred Feather sitting on the seat outside the King's Arms about 1963.

Tom Pye

The seat outside the King's Arms was a regular stopping off point for old timers in the

village when I was growing up. My first recollection of it was when I was taken

down there as a small boy by Fred Pye. He lifted me up so that I could see through

the window into the Tap Room and look at a crocodile skin that was hung on the wall.

At the time Fred's father, Tom Pye, was sitting on the seat smoking his pipe. I have

only a vague recollection of Tom as he died in 1955, but Fred later gave me Tom's

army cap badge from his service during the Great War. I recall Fred saying, with a

wry smile, that his father served with 'Ally Sloper's Cavalry', and for a while that is

what I thought the initials ASC on the badge meant. Tom was, of course, serving

with the Army Service Corps, the force that were engaged in bringing up supplies and

equipment to those that were in the front line. The troops in the fighting regiments

nicknamed them 'Ally Sloper's Cavalry' after a comic, rent dodging, cartoon

character, popular at the time.

When the war broke out Tom Pye was 37 years old and living with his family at

Cragg Farm in Sutton, from where he ran his business as a horse dealer and trainer.

In January 1916 the Government brought in conscription for all men between the

ages of 18 and 41, unless they were married or widowed with children, but in June

they removed the exemption for married men (in April 1918 the age was extended

again to men between the ages of 17 and 51). Although older men with families

knew that they may be called up, it must, nevertheless, have come as something of a

shock when Tom received his call up papers in April 1917, just short of his 41st

birthday. Whatever his feelings were he signed up on 18 April and was assigned to

the Army Service Corps. He passed his medical, despite an entry stating that he had

an infancy trauma contraction - right hand, which was deemed a slight defect not

sufficient to cause rejection. Having given his trade as 'horseman' he was duly

appointed to the horse transport section, where he was to be employed as a driver.

After a brief period with 668 Company at Blackheath, near London, Tom was placed

with the 1st Auxiliary Horse Company and boarded the Troopship “Archimedes” at

Southampton on 8 August 1917, landing at Le Havre the following day. For the rest

of the war he was one of the many thousands that kept the fighting men at the Front

supplied with food, equipment and ammunition.

During 1918 Tom was transferred to the 2nd Auxiliary Horse Company and finally to

the 4th Company. After serving a year in France he was granted 14 days home leave

on 22 August 1918. On returning to duty he remained in France until well after the

armistice and did not return until the 18 April 1919. He was finally discharged from

a base in Ripon on the 17 May 1919. His service record states Military Character -

Good.

The Army Service Corps were present on all fronts during the war, a total of over

315,000 men and over 10,000 officers from all over the Empire, kept the fighting

troops supplied from the Corps Base Depots. They performed one of the greatest

unsung achievements of the Great War, for which in 1918 the Corps were granted the

prefix 'Royal' in recognition of their services.

The Pye family eventually moved from Cragg Farm to the old stables and cottage at

Springfield House in Sutton Lane. They continued living there until after the Second

World War when they moved to Rosewood Square, where they lived into the 1960's.

Fred Feather

Fred Feather was another well known character who occupied the seat outside the

King's Arms during the 1950's and early 60's. He lived in one of the cottages across

the road from the pub and was always pleased to talk to me, whenever I took the time

to sit a while with him. As a small boy I was somewhat in awe of him as he had

'driven' a tank in the Great War, one of those monstrous machines that I had seen at

the Bovington Tank Museum whilst on holiday in 1960.

Sadly his war service records have not survived, so we do not have any information

as to his service in the Tank Corps. However, he had certainly seen some action and

was fond of telling how whilst advancing across no man's land his tank had been put

out of action. He and the rest of the crew were unable to escape through the entry

hatch as they were being raked by enemy fire and so they opened up a small escape

hatch in the 'bottom' of the tank. All the crew members apart from himself were able

to squeeze through the hole, but he was short in stature and amply built and unable to

get out. After some discussion he decided to strip off naked and cover himself with

engine oil, and after passing out his clothes, his comrades managed to pull him

through. Once out of the tank they sheltered from enemy fire and as it grew dark

managed to make their way safely back to the British lines. Fred never tired of

telling me the tale, chuckling to himself as he did.

There is no doubt that Fred and the crew had a lucky escape and it may well be that

his tank had broken down rather than having been hit by the enemy. Tanks had been

quickly developed by the British and were hastily rushed into action before they were

wholly reliable. They were first used a the Battle of Flers-Coulcette, in the closing

stages of the Somme campaign in September 1916, but out of the 49 tanks available

only 32 made it to the Front and of those only nine succeeded in crossing 'no man's

land'. The early use of tanks put terror into the hearts of those Germans that were

unlucky enough to face them. Ralph Hodgson of Steeton, who was serving with the

Tyneside Irish, wrote to his sister in Silsden in October 1916 ... I hear the Germans

are objecting to our latest patent the tanks. Well I think he should be the last to

object to any invention that the Allies may have put on the field & it wasn't like that

when he used his gasses & killed thousands of our poor lads at the beginning of the

war. There was some of our lads telling us there was a whole batch of germans came

over the other day to look at one of these tanks, they waited until they got too close &

then they opened fire on them, there wasn't a single man went back, they mowed them

down like grass.

As the war progressed the reliability of the tank was greatly improved and they

played an important role in the success of the Allied offensive of 1918, breaking

through the enemy lines and enabling the infantry to take full advantage of the

breach. Fred Feather was one of the many lads who suffered the claustrophobic,

cramped and almost airless conditions of these early cumbersome machines that

helped to bring ultimate victory to the Allies. A memorial to the Tank Corps stands at

Pozieres, near Flers-Coulcette, in France where they first went into action on 15th

September 1916.

Fred Feather died in 1964.

Eddie Feather

I never knew Eddie Feather but came across his service records whilst I was

searching for information about Fred Feather and it is possible that they were related.

Eddie was born in Sutton in 1892 and was the son of Thomas and Elizabeth Feather,

his father was a joiner in the village and died in 1906. When war broke out Eddie

was working as a weaving overlooker at Mssrs T & M Bairstows and lived with his

mother at 19 Park Lane in Sutton Mill. He signed up in the Duke of Wellington's

West Riding Regiment in February 1916, perhaps along with his two elder brothers,

Hartley and Willie, and was appointed to the 2/6th Battalion, which had been raised in

Skipton in September 1914. He was not a big man, his medical record gives his

height at 5 feet 4 inches, with a chest measurement of only 35 inches when full

expanded, and he weighed in at only 118lbs (8stone 6lbs or 53.5 kilograms).

Although he was 21 years old he was very small in today's terms, the size of the

modern average 14 year old boy. However, on 12 February 1916 the medical

examiner described his physical development as – Good.

Eddie spent a year in training and on home duty before his Company embarked for

the Front. They left Southampton on 5 February 1917, arriving at Le Havre the

following day. Once in France the Company joined their Battalion, which formed

part of the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division, who were currently located along the

Ancre Front, some miles to the north of Albert. In April, when the Germans made a

tactical withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line, the Division moved towards the village

of Bullecourt. On 11 April the Australian 4th Division advanced to attack Bullecourt

with the support of 11 tanks, all of which either broke down or were destroyed by the

enemy. The attack was a costly failure, but undeterred British and Australian forces

prepared for a further attack on 3 May. The Australians and the 62nd (2nd West Riding)

Division, again supported by tanks left their trenches in the early hours of the

morning under the protection of a creeping barrage from their artillery. The enemy

were quick to respond with return fire and counter barrage. At some stage during the

battle Eddie Feather and two other soldiers were sheltering ... in a dug-out during a

German bombardment when a shell burst near the dug-out and killed Private

Feather's two companions and wounded him in the arm. Eddie was fortunate to

survive and was able to make his way back behind the lines to a field dressing station.

The following day he was sent to Boulogne and two days later he was on board a ship

back to England. He arrived at St Luke's Hospital in Bradford on the 8th May where

he was treated for a shell wound to his right elbow. He was discharged on 12 June

1917 when the wound had healed.

It appears that Eddie spent the next six months getting back the full use of his arm

and once he was declared fit for service he rejoined his regiment in France. He left

Southampton for Le Havre on the night of the 4 December 1917 and on arrival was

allocated to the 10th Battalion, West Riding Regiment, however, three days later he

was reposted to the 2/4th Battalion. He joined his unit in the field on 18 December,

just to the west of Cambrai on the Arras Front. The previous month the 62nd (West

Riding) Division had broken through the Hindenburg Line with the support of the

new improved Mark IV tank, of which 476 went into action. During December much

time was spent securing the new advanced line. In March the Division took part in

the Battle of Bapaume (25 March) and the First Battle of Arras 1918 (28 March). It

was during one of these engagements that Eddie distinguished himself in battle,

following which his commanding officer put his name forward for the Military

Medal. The issue of this medal for bravery in battle had been approved on 25 March

1916 and was the 'other ranks' equivalent of the Military Cross issued to officers.

The award of the medal to Eddie Feather was announced in the London Gazette on 16

July 1918.

On 15 July 1918 the Germans commenced an offensive against French forces at

Rheims, which culminated in the Second Battle of the Marne. Although the French

forces successfully halted the enemy east of Rheims, they were unable to stop them

west of the City. British and American troops, including the 62nd (West Riding)

Division, were sent in to bolster up the French positions and the German advance was

stopped on 17 July. The Allies counter attacked the following day and the 2/4th

Battalion went into action on 19 July at Tardenois. The Germans were eventually

pushed back to the positions that they had held in Spring 1918 and nearly 30,000

prisoners were captured together with 793 pieces of artillery and 3,000 machine guns.

After the success on the Marne the Division returned to the British Front Lines in

August, this time to the Scarpe, on the northern extremity of the Somme Front,

between Arras and Bapaume. The second Battle of Bapaume began on 21 August

and a German counter attack the following day was repulsed. The British

Commander, General Haig, now opened up a 33 mile front stretching north to Arras

and the second Battle of the Scarpe opened on 26 August. On 30 August, the final

day of the battle, Eddie was wounded for a second time and had it attended

to at a field dressing station. The wound was slight and once he was patched up he

was able to return to his unit the following day.

During September the Division engaged the enemy at Havrincourt on 12 September

and at the Canal du Nord at the end of the month. Both battles saw the British break

through the Hindenburg Line, which left the way open for the advance into Picardy.

After this engagement Eddie received a welcome break and was granted 14 days

home leave, he went home on 12 October 1918 and returned on 26 October.

On 4 November 1918 Eddie and his Division took part in their last battle of the war,

at the Sambre Canal. It was a desperate and bloody affair (during which the poet,

Wilfred Owen, was killed leading his men in an attempt to cross the canal). Eddie

survived and the war ended seven days later. However, the armistice on 11

November 1918 was not the end of military service for Eddie. Under the terms of the

armistice Germany had surrendered unconditionally and was not invaded and

therefore a substantial number of troops remained in France until well after the Treaty

of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. Eddie enjoyed a further 14 days home

leave before he left France for good on 2 September 1919. He was finally

demobilised at North Camp, Ripon on the 12 September 1919. Eddie Feather died in

1963 aged 71 years.

Note: Principal sources :– National Archives - military service records and WW1

medal cards; Keighley Reference Library – Keighley News; London Gazette online;

The Long Long Trail – online WW1 recourse; and author's recollections of Tom Pye

and Fred Feather.

With thanks to Robin Longbottom for providing this article. November 2012.